Flavours of the past

There was a wedge of time - a period of about 18 months - when we cooked, and ate, a lot of Moroccan food. Marrakech was a city I fell for at first sight: close enough to be reachable for short breaks but a world away from home in terms of temperature, culture and food. It has an aged and confident energy, particularly in the cloistered surroundings of the Medina, where unmappable streets guarantee the prospect of getting lost and idyllic riads hide behind the most unassuming doors. Several times a day, the call to prayer echoes over the city - loudspeakers whirring like a fleet of helicopters taking flight, one after the other - and you know, immediately, that you are somewhere that isn’t home.

And just as the city did, the food resonated with me. Piles of cous-cous, slow-cooked meats, roasted on spits in coal ovens and the specific interplay of savoury and sweet and spiced that dominates much of the culinary canon there. It’s a style of cooking that we see little of here where often spice rubs along hand in glove with heat. Moroccan food has little need for chillies, instead taking the spices of the old trading routes as its flavour base. Cinnamon, cloves, anise and cardamom are used in savoury dishes with a generous hand and it is common to see honey (or sugar) used liberally with meat.

We bought a couple of tagines (from John Lewis, rather than the souks for no reason other than the in-generous Ryanair baggage allowance), perfected cous-cous making (cold water is the key) and then ate chicken with preserved lemons, or beef with apricots at least once a week for about a year.

We see very little of that flavour profile in British cooking. It wasn’t always the way. The Forme of Cury, the famed 14th century cookbook from the court of King Richard II, positively heaves with savoury recipes containing warm spices, rosewater and ginger. What better way to make conspicuous displays of one’s wealth than by importing and cooking with handfuls of exotic spices bought at tremendous expense? Fashions changed over the next few centuries and now, often the only use we have for cinnamon or cloves is in the pastry kitchen and unless it’s apple sauce for pork, rarely do we venture to pairing fruit with meat (game is an interesting exception to this, where we think nothing of serving venison with blackberries or duck with cherries).

Which is a shame, because there is something comforting about those particular flavours, especially when it comes to dishes where the ingredients have spent a long time getting to know each other. Food that melts into itself is a genre that brings particular joy at this time of year: low effort, high impact cooking that requires little tending in the oven and doesn’t care if you stay for another pint or one more round of rummy.

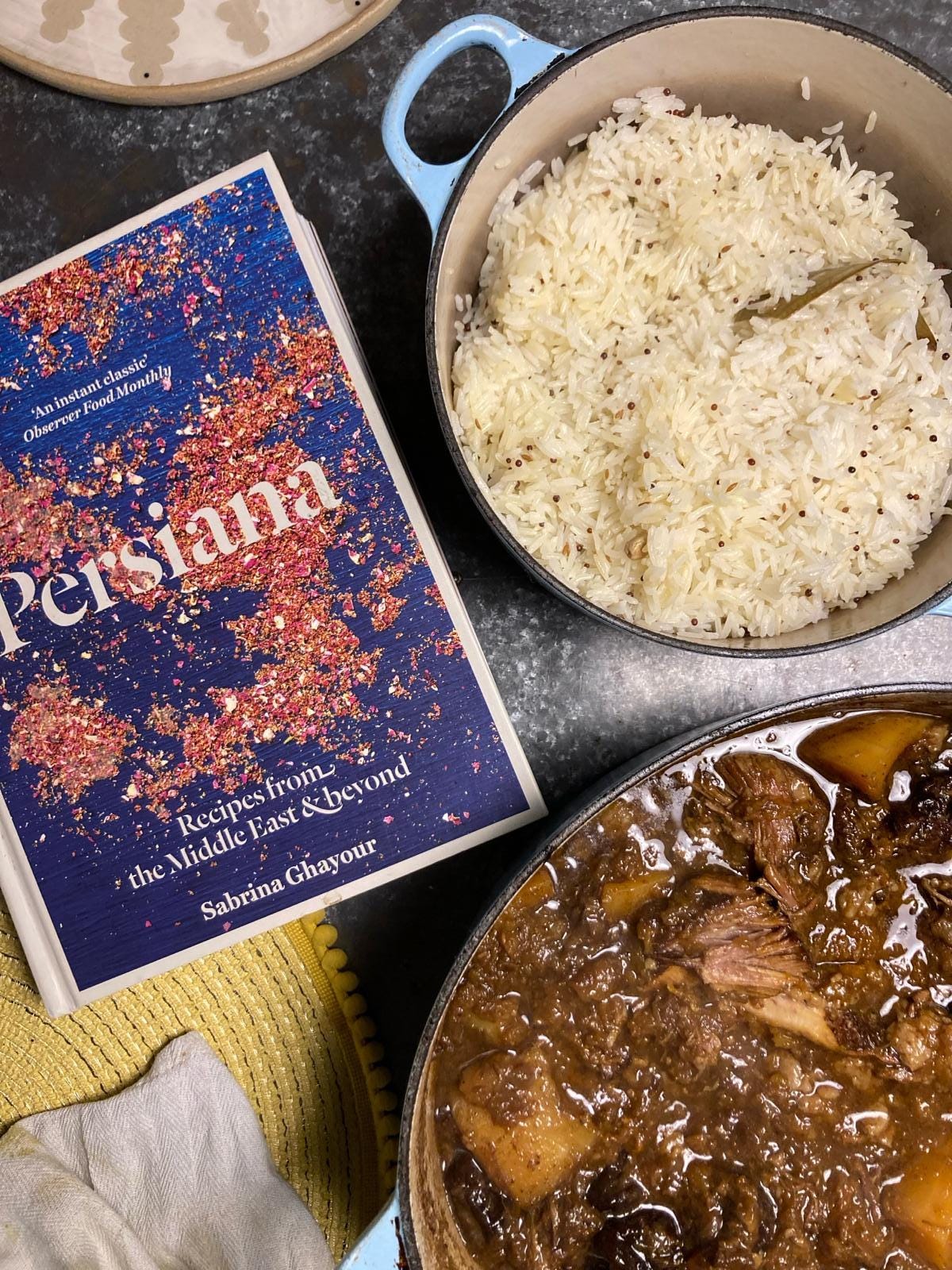

This is all a roundabout way of saying that, after an absence of a couple of years, I made a tagine from Sabrina Ghayour’s magnificent book Persiana. Lamb, prune and butternut squash in happy harmony, rich meat rendering into a fatty sauce tempered with sweet prunes and chunks of locally grown squash. There were other recipes, too. In fact, Persiana was the final book I got to when the project stalled in August last year. I accomplished the cooking aspect and then lost track, forgetting that I’d done the experiment, but had failed to write up the results. There was a herb-laden pilaf, green beans with figs and a delightful dip made from feta cheese and pistachio nuts, all of which were prepared for family meal at the restaurant one day in high summer, recipes so flavourful I can recall them now. But it was the familiar flavours of the tagine that that I enjoyed the most.

I embarked on this project to cook new things and bring fresh ideas to a repertoire that I felt had become a touch stale and jaded, and that has been an important element in this project. What I didn’t expect was for it to remind me of old favourites evocative of a spice-laden trip a decade ago and those first memories of Marrakech.